A view of New York City, with the Freedom Tower at center, from New York Harbor.

You see plenty of small brown objects on the sidewalks of New York City.

Most of them don’t deserve more than a glance as you step widely around it on your way to work, school, museum, theatre, crackhouse, or restaurant. But this one, which I came upon as I was walking to my office one day during the week between Christmas and New Year’s, was different. The breeze blowing in from the Hudson River and keening through the gray canyons of Manhattan were ruffling the feathers of the little woodcock, which was laying, dead, between a mailbox and a food cart on 31st Street, just a spit away from its intersection with Broadway.

I knew it was a woodcock, because I’ve been around them all my life.

The woodcock is a bird of woodland thickets, secretive and camouflaged to match its natural habitat, which midtown Manhattan is not. But there’s a reason I found this one.

The first wild game bird I’ve ever shot was a woodcock, when I was 15 years old and hunting the damp woods around the Passaic River suburbs in northern New Jersey. I still have a tail feather from that first bird, and the envelope I saved it in, after reading the recommendation from H.G. Tapply (of Field & Stream’s “Tap’s Tips” fame of years ago) that pulling one from each bird is an easy way to keep track of the number of birds you shot every season. (As if I would have shot dozens–isn’t the optimism of youth wonderful?)

I had high hopes (but low results) when I was a 15-year-old hunter.

I had crept up on a peenting male in a meadow one spring evening, part of an assignment in a wildlife biology class at Penn State. I’d heard the same odd, unique sound in a quiet, overgrown field across from a condo I lived in outside of Princeton, as the males would spiral up into the night sky in their mating ritual. I’d flush one occasionally while scouting for deer or hunting for small game. Once in a while, I’d actually shoot one and prepare it for a small dinner.

So the question I asked myself that cold early morning on the grimy sidewalk, as bundled-up commuters hurried past was: Why? Why did this bird of alder thickets and young moist forests, with its long bill designed to probe for earthworms in loamy soil, wearing mottled feathers that perfectly match the leaf litter of its secluded habitats, choose to fly directly over the biggest, busiest, brightest city in the country? And obviously not survive the trip?

“I seen that thing around,” a fellow pedestrian said, seeing me bent over the bird with cell phone in camera mode.

I was surprised someone else had noticed, and wanted to know more. “Where?” I asked.

“Around here,” he said.

“On the ground, you mean? Or flying?”

“Around. You know?”

I couldn’t be sure if he was confusing the woodcock with one of the city’s brown pigeons, or if the woodcock really had landed here on the sidewalk, with 10- and 20-story buildings all around. It really didn’t matter; it was dead.

I took a quick photo of the bird on the sidewalk, picked it up, plucked a tail feather, and carried it to the street corner. Wrapped in newspaper and placed in a New York City trashcan was a very unceremonious end to a bird of a species that I’ve always revered, so I vowed to find out why a woodcock would ever fly over Manhattan.

And I did find out.

* * *

The woodcock is a creature of habit. Anyone who has hunted them for a while knows that you can find woodcock in many of the same places, autumn after autumn. Their earthworm diet means they need damp, soft ground so they can probe for earthworms, but also with just enough overhead cover to camouflage them. One fall, hunting the base of a ridge in northeastern Pennsylvania, I kicked up a woodcock from a depression in the ground not much bigger than a utility sink. I totally flubbed the easy going-away shot. The next year, hunting the same bottom, another bird (maybe the same one; who knows?) flushed from the very same hole. Having had approximately 364 days to prepare for the shot, I managed to drop that one.

Woodcock, apparently, are also slow to adapt to changes–changes such as a teeming city being built in the middle of an historic flyway. That’s apparently why I found this woodcock just a few blocks from the Empire State Building—less than a ten-minute stroll to where one million cold and mostly un-sober people hoot and cheer every midnight on January 31st as a glass ball descends a spire in Times Square at midnight.

Manhattan Island was probably a terrific place to hunt woodcock about 400 years ago—all those thickets and freshwater marshes must have made it one giant covert sitting out in the Hudson River. (You can’t hunt woodcock in the Big Apple now, of course. All that pigeon scent would confuse your dog’s nose, and any birds you do flush would inconveniently level off right at stoplight height.) But the birds still fly over. And I wasn’t the only person who had found a dead woodcock in the middle of the Big Bad City.

Michael Schiavone is a wildlife biologist with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. He’s the guy who gets the letters and emails with photos of a woodcock lying at the base of a skyscraper, along with the question “What is this bird?”

He wasn’t surprised to hear of my Broadway woodcock, and had a ready explanation.

“They’re low-altitude migrators, and they fly a lot at night,” Schiavone told me. “It may have become disoriented.”

I’d known woodcock were low nighttime flyers, having stood at the edge of a New Jersey thicket one evening in late October and watched one woodcock after another pitch into the woods, their silhouettes backlit by the moon. But why fly directly over a city?

“There’s a big corridor up the Hudson River valley,” Schiavone said. “Your bird was probably following it.”

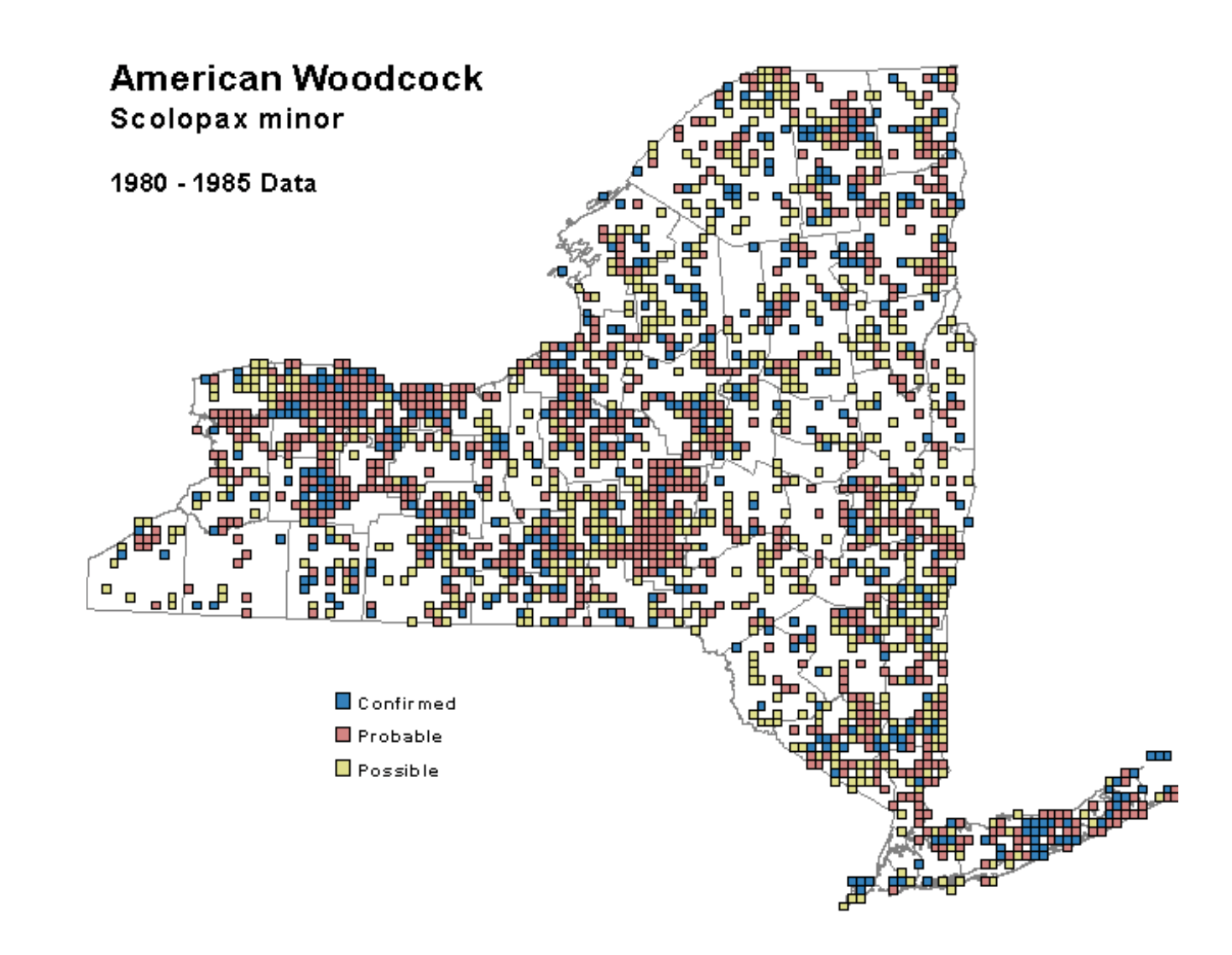

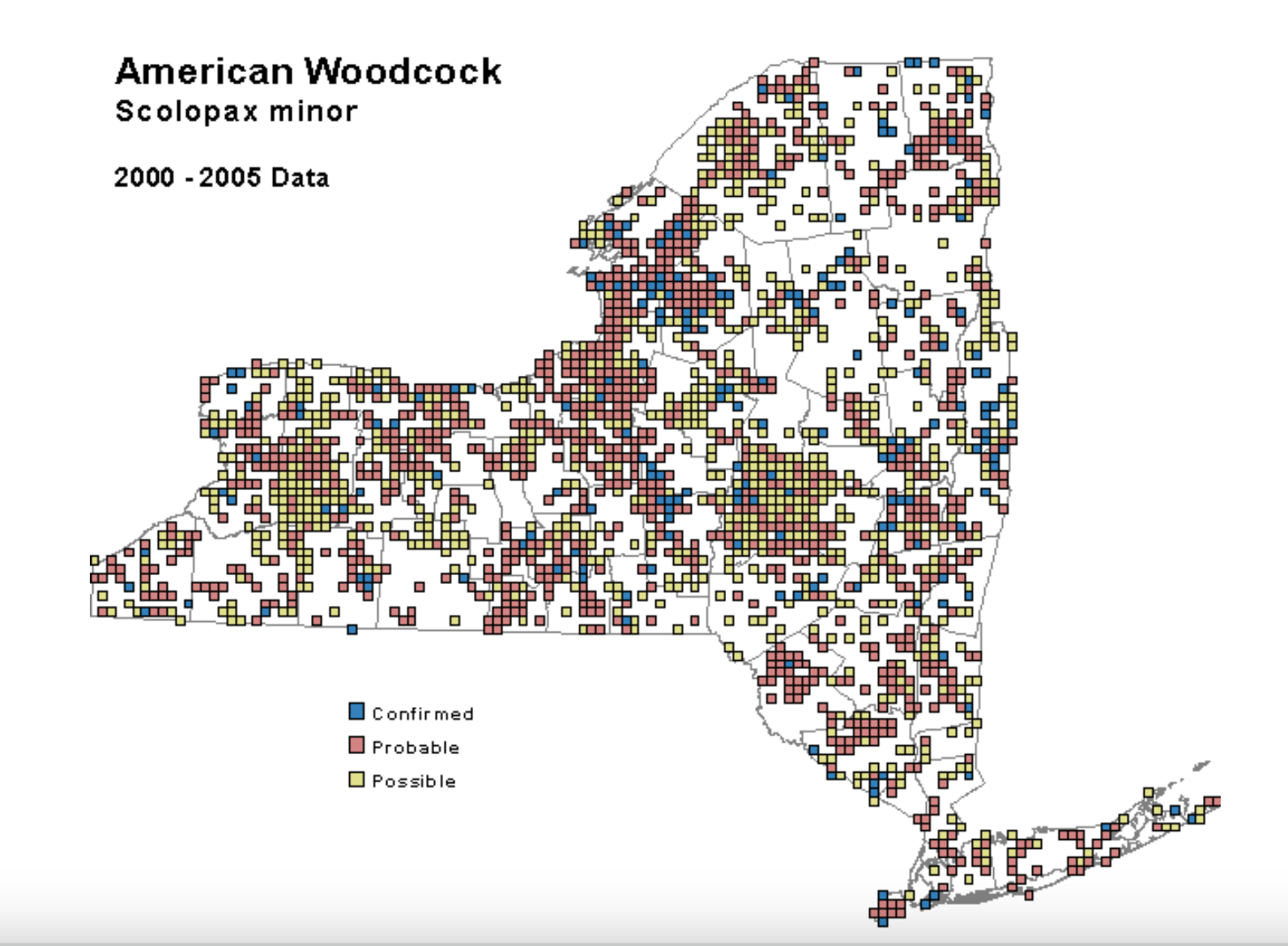

Schiavone sent me maps that recorded woodcock sightings throughout New York State from 1980 to 1985 and again from 2000 to 2005. Neither map notes birds seen on Manhattan, but Staten Island—which lies directly southwest of the city, just across New York’s Upper Bay, home to Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty—is covered with sight denotations.

While Staten Island isn’t exactly bucolic, it has plenty of woodcock-friendly fields and woodlots. And the shortest route to Staten Island from the Hudson River valley goes directly over Manhattan.

Light pollution has been long known as a bird killer. My guess is that the city lights had confused the woodcock I’d found, as Schiavone theorized, hit a building, and fell to the sidewalk. Its injuries weren’t immediately fatal, but severe enough to keep it from flying. That would explain why the guy who saw me photographing the bird said he’d seen it in the neighborhood days before.

The bird had assuredly succumbed to cold and starvation; the closest earthworm (actually, the closest earth) being in a small park almost a mile away. What’s amazing is that the bird was intact—it hadn’t been run over by a taxi or a bicyclist, which is the fate of most injured pigeons in the City.

I put the tail feather of this bird in its own envelope and put it in the shoebox with all my old hunting and fishing licenses and harvest tags. It was, after all, a bird I’ll never forget.