© 2025 Mike Toth

It’s the kind of room you’d expect to see in an old commercial building in a small town: plain wooden walls, a concrete floor, benches and shelves overflowing with metal parts and tools. There’s no window.

There’s not even a desk. It’s a working room, filled with tools and equipment. A room where you make things, like furnaces and engines.

There’s also no sign of Peter Benchley, no aura of what he made in this room: a novel that stayed on the New York Times bestseller list for 44 weeks, fascinating millions of people and simultaneously making them fearful of swimming in the ocean. This is the novel that, along with the movies it spawned, changed the world’s view of sharks—for the better, eventually.

The room is 22 feet long and 14 feet wide, and I can picture Benchley, back in 1975, getting up from his typewriter and pacing out the 20 feet that his great white shark measured.

“Huh. I never measured this room,” says Mark Blackwell, who is holding the other end of my tape measure. “That’s interesting.”

Blackwell owns this building and the property, which used to house the Pennington Furnace Supply Company. There’s a window with that name on it out front, the old black lettering camouflaged by equipment behind it, but still legible. Another window on the building spells out Blackwell’s Garage in newer red, white, and black paint, which is Mark’s business now. He makes automotive racing equipment. When I walked in earlier this year, he was installing bearings in a differential.

Blackwell used to mow Benchley’s lawn over on Birch Street when he was a teenager. He would see Benchley here in this room, occasionally talking to Mark’s father, Thomas W. Blackwell, who owned the furnace supply company and rented the room (which is in a one-story building—there is no “above” room, as incorrectly cited on the Peter Benchley Wikipedia page) out to the author.

“My father and Bill Howe, a neighbor, would sit here with Peter Benchley and the three of them would play rummy,” says Blackwell. He doesn’t have any memories of Benchley actually working on the book—he was, after all, a teenager with interests more important than watching a guy bang out words on a typewriter. But he does remember Benchley holding up a copy of Moby Dick and saying “This is where I got the idea!”

Why would Peter Benchley, whose estimable pre-Jaws career included being a speechwriter for the Lyndon Johnson administration and a magazine editor, rent a room in a busy, noisy, furnace supply shop to write a novel?

The room was a mile from his house—an attractive converted carriage house in a quiet neighborhood of a small New Jersey town, across the street from a leafy woodlot. It’s the kind of house you picture when you think of the quintessential writer’s space, Thoreau-like in its solitude, splendorous nature outside the window, a place where one can think widely and create freely.

The answer is something that many workers found out when Covid forced millions of us to toil in home offices: too many distractions. For Benchley, it was his two rambunctious boys, says his wife, Wendy, in a fascinating interview with Ross Williams of The Daily Jaws. “He had been a reporter for Newsweek for years, so he was used to a lot of clank-clank-clank of old-fashioned typewriters in those days,” says Wendy, who was home with those kids at the time. “So being in the furnace repair shop was much better for him, much calmer than hearing children screaming.”

The desk that Benchley used is still here. It’s in another room, and when I look at it, I don’t feel any writer vibes coming over me. It is, after all, just a piece of office furniture, a place for a man to sit at and work.

Benchley’s desk where he wrote Jaws.

Benchley needed to work, because the family needed the money. “He was writing speeches for President Johnson, and then when Johnson decided not to run again, Peter decided to freelance,” Wendy says. “We ended up in a little house in Pennington, New Jersey. He was doing freelance articles for magazines and honestly not making enough money to support me and two children, and I did not have a job at that moment.”

Benchley had a couple of ideas for novels, says Wendy. The one about a huge great white shark that preyed on swimmers at a coastal beach town, during the height of the summer tourist season, was most interesting to people—and to Doubleday book editor Tom Congdon.

Wendy wasn’t convinced. “‘Oh gosh, Peter, I just don’t think it’s that great an idea,’” she remembers saying at the time.

Congdon gave Benchley a $1000 advance for the first 100 pages of the book, and Benchley began writing. His inspiration, according to Benchley’s obituary in the New York Times, came from a from a news article he had read about a fisherman who had caught a 4,500-pound great white shark off Long Island in 1964. That fisherman was Frank Mundus, a charter-boat captain that specialized in shark fishing. Benchley fished with Mundus many times in the 1970s, and apparently used a lot of those experiences to frame the fishing scenes in the novel and the movie, including how Mundus would tie barrels to the end of harpoon lines so he could track sharks as they swam off.

Benchley knew something about fishing. As a kid, Wendy says, he spent many summers in Nantucket and would go fishing with his father, author Nathaniel Benchley. Often, when they’d have a fish on the line, a shark would eat it before the two would have a chance to get the fish in the boat.

Another thing Benchley learned from his summers in Nantucket: how local businesses relied upon the tourist trade in the summer months in order to make a living there year-round. That reality, of course, also made its way into the novel, with Amity mayor Larry Vaughan threatening to fire Chief Brody if he closes the beaches to prevent more attacks from, as he euphemistically described it, “a large predator.”

Mark Blackwell, who has lived in this town of 2,700 people all of his life, says that Benchley would ask his father Thomas a lot of questions about shark fishing. The elder Blackwell went deep-sea fishing off of the New Jersey shore, which is about an hour away from Pennington, and knew something about going after big fish from a boat—a handy reference for Benchley.

Throughout all this time, no one had any idea how momentous the book would be. Actually, no one was even sure that the book would even be published. Peter kept writing, and life went on in Pennington with the Benchleys.

That all changed when editor Congdon, after several rewrites, approved that initial first section of the novel, and wanted Benchley to finish it. Jaws was going to become a reality.

Wendy’s reaction? “I cried,” she says in the Daily Jaws interview. “I thought my life was ruined. I just loved my life in Pennington with Peter and the two kids, and I was in the League of Women Voters, and I felt that it was just wonderful if we could just keep going. And I had seen, and so had Peter, other people who had basically been spoiled or their life ruined by too much notoriety, and so I was hesitant about that. I really didn’t want to get into that world.”

Downtown Pennington, between the Benchley’s home and Pennington Furnace Supply.

That reaction is easy to understand when you walk the streets of Pennington between Benchley’s old house and the furnace supply company. It enables you to see what the Benchleys’ world was back then. The leafy streets are wide and quiet, lined with well-kept brick and clapboard houses with porches and wide lawns. Kid ride bikes here, some to the elementary school on Main Street. The main intersection in town, even now, has only a bank, a bakery, a pharmacy, a small pizzeria, a couple of salons, a manicurist, and a second-hand clothing shop. The speed limit is 25 miles per hour just about everywhere. Temporary signs along the sidewalk advertise events such as the Pennington 5K race and a pancake-breakfast fundraiser for the fire department. Joanne Blackwell, Mark’s wife, is a school crossing guard.

It’s a town that young families move to, enroll their kids in schools and sports leagues, get involved in civic activities, put down roots. But such a future was not in store for the Benchleys, and Wendy got a sense of that when the novel was released and began its dominance on the bestseller list.

“When suddenly you’re in the news,” Wendy says, “people talk to you differently. (In) the League of Women Voters, I always used to have really good strong arguments about public policy issues, and what we should be doing about recycling or one thing or another. And some of the women I knew sort of pulled back and wouldn’t argue with me anymore.”

Wendy points out that once she got over her trauma of how her life was going to change, she realized how the novel could change their lives for the better. When they learned that Richard Zanuck and David Brown at Universal Pictures wanted to make a movie based on the book, and asked Peter to write the screenplay, that life change accelerated.

It also instituted the beginning of an obligation that Peter and Wendy felt to protect sharks and the world’s oceans.

“Peter often said it’s not often that a novelist can write a novel, and then it takes him into a different world,” says Wendy. “That book enabled us to go out on expeditions with the National Geographic, with American Sportsman (an outdoor-sports oriented program on ABC) and see with our own eyes what was happening in the ocean. That was in the 1970s, when we really hadn’t done much scientific research into what was happening to sharks and the ocean itself. We very quickly saw there was a lot of shark finning going on, a lot of pollution. That was when people started to realize we have got to take better care of our ocean, of our planet, and so, lucky us, that was one of the end results.”

The Benchleys moved from Pennington to nearby Princeton, where Peter continued writing and Wendy became involved in politics. She was elected to the Mercer County Board of Chosen Freeholders, and then was elected to the Princeton Borough Council, where she served three terms in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Peter went on to write several other novels—The Deep, Beast, White Shark among others. He also wrote Shark Trouble, which sought to alter the general public’s impression of sharks as evil, bloodthirsty creatures and instead illuminate the role of sharks in the world’s complex ocean ecosystem. That corrected perception still stands today.

* * *

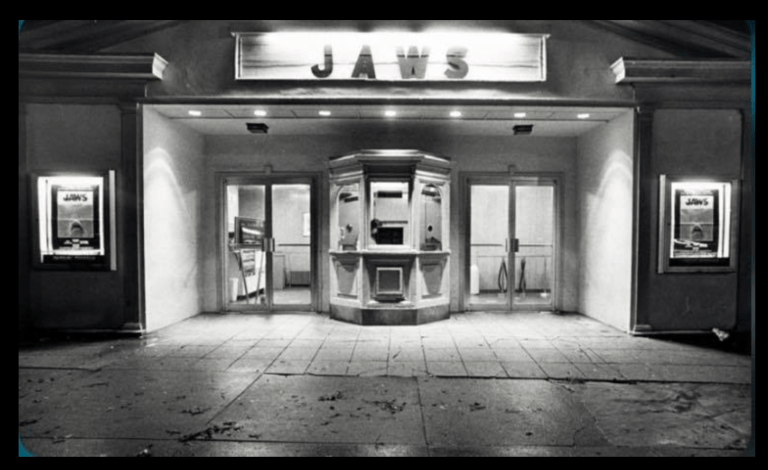

Mark Blackwell saw the premier of Jaws at the Princeton Garden Theatre, just a few miles away, in 1975. He remembers how cool it was to see the movie based on the book that was written in the room in which we’re now standing. In 2021, the theatre showed the movie again. It was so popular that the theatre booked an encore.

The Princeton Theatre when it premiered Jaws the movie in 1975.

I’m more than a little surprised to learn that in the 50 years since Jaws was published, not one person has asked to see this room. “Nope. You’re the first,” says Mark Blackwell.

I tell Mark that I think many people would be interested in seeing this room, to see how modest is the space where a novel of incredible magnitude was turned out by a genius of a writer. Mark looks around the room and gives me a funny look. “Why?” he asks.

I want to tell him that the novel and the subsequent movies have fascinated so many people, over so many generations, that they might think of this place as a sort of shrine to visit.

I want to tell him that they might want to see this room and picture, as I did, Peter Benchley sitting at a plain office desk, typing words on paper, words that ended up thrilling and captivating millions of people.

I want to tell him that what was created in this room made us all perceive the ocean in a totally new light, and eventually made us want to protect sharks, revere them for the magnificent creatures they are.

I want to tell him how the novel led to something called Shark Week, a week-long block of shark shows, movies, and documentaries on the Discovery Channel that began in 1988 and has become the longest-running programming event in cable TV history.

I want to tell him that many people make it a point to watch Jaws every year (as my wife and I do), and it’s still fascinating and moving—and still scary.

The set of The Shark is Broken, complete with one of the yellow barrels used during the filming of Jaws.

I want to tell him that it led to a Broadway show called “The Shark Is Broken,” which depicts the boat scene in the movie set and reveals the friction between actors Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, and Richard Dreyfuss on board as they endure long waits together while the mechanical shark was undergoing repairs.

I want to say that some show-goers, young people in their 20s, born 30 years AFTER the book was published, went to that play dressed as Hooper in an homage to the brilliance of the story.

But I don’t say any of this, because I know that Mark Blackwell has to get back to work. After all, I’ve interrupted him at his job. Just like Benchley did here, he has things to build.